State of Limbo

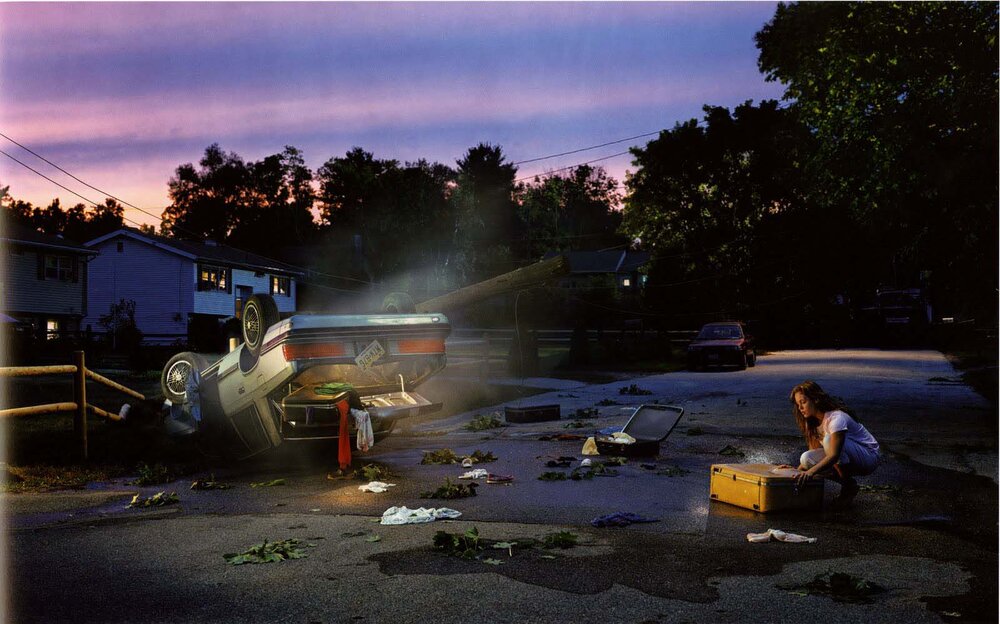

Not one picture exists in an isolated second – it is the duration of many moments. The pictures are the moments in between moments, too, which are the times where you are lost between two different things; a state of limbo.

Gregory Crewdson

Published October 24, 2016

the Paris Review

Gregory Crewdson is a photographer, but he calls himself a storyteller. He has spoken of his belief that “every artist has one central story to tell,” and that the artist’s work is “to tell and retell that story over and over again,” to deepen and challenge its themes. True to this, Crewdson’s most recent body of work, Cathedral of the Pines, shares the aesthetic that has defined his career—cinematic scenes of domestic life in the Berkshires—but the images have quieted down. While once Crewdson burned down houses or called the police on himself in order to photograph officers, his concerns have shifted lately from the spectacular to the murky and internal.

The hallucinatory images for which Crewdson is best known—sod laid on living room carpets, crop circles and house fires, or tight beams of light emerging from a blank sky—evince the magnetism of catastrophe and the titillation of the strange. Those older works defined Crewdson’s signature style of cinematic production values applied to suburban surrealism and made him one of the most recognizable and influential contemporary photographers.

Now in his midfifties, and coming off a six year hiatus from photography, Crewdson’s aesthetic hasn’t changed so much as deepened. His influences are still apparent: Spielberg, Lynch, Hopper, Cindy Sherman—artists who estrange the quotidian, fixate formally and thematically on windows, and reference movies that don’t exist. But his new work eschews the thrills of the old in favor of a bleak psychological realism.

You talk about literature being influential to you. Will you tell me who your favorite writers are and what you like about them?

Raymond Carver and John Cheever. That brand of American realism.

Above all it’s their exploration of the ordinary, the familiar. I think with Carver in particular it’s the idea that you can find this sense of drama in a small domestic event, and it can be magnified and made transformative in some way. I see my pictures as being very much aligned with that, taking a familiar situation and making it dramatic, in my case through gesture and color and light. And then, of course, giving the impression that everyday life is unsettled in some way, or made mysterious or wondrous somehow. I guess the story I most identify with is Cheever’s “The Swimmer.” And for obvious reasons—number one, I am a swimmer. But it’s also the obsession in that story, and the hallucination of it, too. It’s realism meeting a psychological strangeness—it’s all located in a sort of familiar landscape and terrain, but it’s transformed. The irrational activity of swimming home through the neighbors’ swimming pools is similar, in my mind, to the act of making the dirt piles in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It’s that same attempt to find meaning in a world that feels alien, trying to make sense of a world that you feel disconnected from. What I love about Cheever’s work—and Carver’s, as well—is that it’s grounded in something literal and ordinary. Of course, the main difference between those writers, or any other writer, and me is that I don’t have the luxury of a linear story. My medium is a suspended moment. So the question then becomes, How do you get everything, all those associations, in a single image, frozen and mute?

You insist that your pictures have no before and no after—that they’re not narrative. What is that distinction you’re drawing between narrative and storytelling?

Yeah, I mean that’s the question, really, in the end. And I don’t really have an answer except for the fact that if I look at the progression of my work from the early images through my most recent pictures, there is definitely an attempt to distill that story more and more as time goes on. If you look at Twilight, for example, when I first started using cinematic lighting and I became more engaged with narrative, the stories were more literal and explicit. The lighting was more hyperbolic or more saturated, and I think partially it’s because at that time I was intoxicated by the possibility of using light in cinematic ways and using cinematic production generally. But I think for each body of work, the story that’s being told becomes increasingly more submerged and interior. There’s very little actually happening in any of the new pictures—they’re emptied out of conventional storytelling, I think.

Gregory Crewdson 2014

How do you know when you’ve submerged too much? Have you ever made a picture where you’ve buried the story to the extent that it doesn’t communicate?

No, usually it’s the opposite. Usually it tells too much. Some of my biggest, most extravagantly produced pictures have never seen the light of day because I went too far. You know, I made things too explicit or too spectacular.

There are a lot of moments where, instead of focusing on a big, active event, we look at something internal that’s happening with a character in the aftermath of that event. I think those are the types of moments he likes to focus on in general.

Do you feel like you’re leaning on language and image in different ways, to serve different roles in the screenplay?

Hiam: Hopefully it all works together as a whole, but the way Gregory thinks about light is very psychological. In previous screenplays, I’ve rarely written about light in this kind of detail, but light is a very important script element for him. When I think about how he works with light, I think of what happens when you walk into a certain kind of a light in the forest and it’s coming down on you and it causes you to have some kind of psychological moment because the light is so unusual or uncanny or unexpected. You can have a shift in understanding because of light in moments like that. I think that’s sort of what happens to the characters in his pictures and in the movie—something internal is brought out by the way they look in the frame, the way the light is hitting them, and we, as the viewer, have that experience that this is an uncanny moment. Without the light, it would be unremarkable. There would be no story.

Cathedral of the Pines

Published 2016

Cathedral of the Pines, a body of photographs, from 2013-4, that juxtaposes the banality of human existence with desolate scenes of deserted buildings in the small rural town of Becket, Massachusetts and its surrounding forests. There are hidden narratives in his photographs, visual documentations of how people feel and find meaning, even in the most desolate of territories. The common theme of Cathedral of the Pines is discomfort: gazes never meet, there’s blood in the sink, and bare flesh is exposed to the snow. The only relief is in the beauty of the pictures themselves, the complexity and specificity of light that Crewdson has spent a career learning how to evoke.

Harriet Nestor: Your exhibition Cathedral of the Pines, which comprises works produced between 2013 and 2014, meditates on ideas of isolation and how humans might behave in desolate, natural environments. Do the photographs seek to reveal the poignant realities of these figures?

Yes, the entire body of work comes down to a number of themes but, at its core, is a search for internal meaning.

So it’s quite existential?

I think so. I was going through a difficult time in my life while making these pictures. My marriage ended, I left New York, and moved into a church near where the photographs were shot. At this time, there seemed to be a lot at stake in my life – there was a period, at least a few years, where I wasn’t able to make work, the equivalent to writer’s block. So when I was finally able to start this body of pictures, it was all very defined in my head.

It could be interpreted that there is a thread of autobiography in this series that derives from experiences in your childhood, which adds another layer of your presence to the series. Can you reflect on your emotional journey while capturing these images?

Yes. I think there is always a relationship between life and art. My pictures are never directly autobiographical, but they do derive from my psychological anxieties, fears and desires. In this particular series, they feel very close to home, especially in relation to what was happening at this time in my life. They are all made in Becket, where my family had a country house, for example. The figures in the photographs are all people whom I know and love. Yet they are not about any of this personal narrative particularly – that is just the backdrop to build a fiction in the series.

The French philosopher Roland Barthes said: “A specific photograph, in effect, is never distinguished from its referent.” Do you think these photographs demonstrate a similar trajectory, in that they originate from an environment that is nostalgic for you? Is solitude at the heart of these images?

For me, solitude is tied into the medium. Speaking of Barthes, I think, generally (which can be a simplified statement), most photographers are drawn to the medium by some separation they feel from the world. Photographers never quite seem to be at home in the world, and yet the act of putting a camera in front of one’s eyes is an act of separation. That theme runs throughout my pictures, but I do also think photographers want some sense of connection. Those two things come together in this series: a sense of being alone, while also wanting to feel connected.

Many of your photographs have been compared to the paintings of Edward Hopper. The idea of being anonymous is often something considered to be symptomatic of living in overpopulated environments, such as cities. However, in your photographs, the dominant environment is a natural one, where figures are suspended in a remote narrative, but yet also feel somewhere unattested. Do you direct the subjects as to how to behave?

I am always conscious of the relationship between the figure and the space – that, to me, is key: how does the figure exist in the larger setting, whether it be an interior or a landscape? For instance, within an interior, there is also a relationship between the figure, the interior space and the exterior space, which all become part of a visual equation. Trying to find a perfect balance between all three is a great challenge in my practice.

Is the composition something you plan while taking the photographs, or do you do so beforehand?

I plan it beforehand, which requires an awareness of finding the perfect symmetry within the photograph – where the figure exists in that particular space at that time.

Is that quite intuitive for you as an artist?

Yes, very much so. Then, in a landscape, it’s more about a sense of scale – how the figure is dwarfed by the landscape and the vastness of nature.

Yes, there is a real sense of physical fragility in Cathedral of the Pines. Despite being in the forests of Massachusetts, many of the photographs have traces of civilisation, such as cars. Is there a feeling that these figures are moving through the environment, as opposed to living within it?

I think you are right about that – the photographs are somewhat transient. There are also a lot of makeshift homes, where there are sheds, outhouses.

Which don’t feel as though they could be inhabited for a long period of time.

Yes. It is a human impulse to create a home for yourself, wherever you are in the world. That’s a theme: how do we create security and meaning for ourselves? Which really, in essence, suggests a longing for a sense of belonging, which made perfect sense for me a few years ago, as I was searching for home in my life.

There is an elongation of time in your photographs, in that the temporality before and after the capturing of the figures in this particular moment marks their embodying of space in a certain environment. In the photograph The Pine Forest, through the posture of the woman in relation to the positioning of the car, there is the suggestion that she is contemplating something. Is there a temporal element in your work, to create a feeling of longing?

Well, first, I think elongation of time is really important because all the photographs are composites because we are always changing the focus. Not one picture exists in an isolated second – it is the duration of many moments. The pictures are the moments in between moments, too, which are the times where you are lost between two different things; a state of limbo.

Is that idea of multiple moments reflected in all the images being the same size and how they are displayed? Almost like a film reel?

Yes. The size of the photographs was very important to me. In Beneath the Roses (2003-7), which was a larger-scale body of work, the prints were incredibly big – panoramic and cinematic, like a movie screen. These in reference are smaller, more like paintings. I wanted them to feel like a suburban window, a sense that the viewer is looking into a world.

Yes, there is a simplicity in the presentation of the images. The titles of the photographs are very literal, too, such as The Haircut, The Mattress and The Motel. Is this linguistic choice purposefully enacted to maintain a realism in the photographs for the viewer? It seems to move away from an ambiguous territory.

I wanted the title of the entire body of work to be poetic. Cathedral of the Pines is a trail name I came across while cross-country skiing. Because it was a trail, it suggested moving through something. The picture of the boy with the skis, also called Cathedral of the Pines, is of this specific trail. So, to contrast that title, I thought it would be nice to have simplistic and direct descriptions of what we are seeing in these images. I didn’t want there to be any room for interpretation, which also plays on a tradition in painting.

Can you say more about this relation to naming of paintings and their traditions?

I am always interested in the viewer creating their own story. In this series, I am not preoccupied with interpreting what the picture necessarily means, which does not help the viewer in any way; it is the most basic element of what you are encountering visually.

Some of the figures are naked. How does nudity operate in these photographs?

Generally, there aren’t a lot of clothes in the photographs. Initially, I wanted this series to be about flesh. I think that is evident in every single picture. When there are clothes, they suggest a vulnerability; a bra, underwear, a dressing gown. Because of the artistic references I was looking at, such as Hopper, and how nature is represented in these paintings, I wanted to see flesh and flesh’s relationship to the natural world. But I think it makes the figures feel more vulnerable – there are naked bodies, young bodies and ageing bodies that raise ideas of mortality. All of this is meant to make the figures seem more vulnerable.

Yes, it feels like a commentary on the human condition, vulnerability. And perhaps on that vulnerability being the state where a search for meaning in oneself originates – when you are caught off guard emotionally, perhaps, which seems quite generous to the viewer.

Yes. For me, it was definitely part of being unable to separate life from art. These images were very much part of a time where that was not possible for me.

Does it feel as if they are a byproduct of a chapter in your life that you now look back on, like a diary entry?

Yes. It is always that way, and I look back on older bodies of work and think that I would never remake pictures in the way I once did. Whether or not I like them is irrelevant. It’s about recognising that I wouldn’t approach art in the same way now.